Nov. 9, 2018

Research gives a voice to family members as war veterans transition back to civilian life

In the Memorial Chamber in the Peace Tower on Parliament Hill, there are seven Books of Remembrance. Together, they commemorate the lives of more than 118,000 Canadians who made the ultimate sacrifice while serving in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in Canada or abroad. This Sunday, Remembrance Day, will mark the 100-year anniversary of the end of the First World War. Canada’s last veteran of that war passed away in 2010. However, there remain an estimated 649,000 Canadian veterans.

Few of us understand the overwhelming loss experienced by those who have served and survived, and the loss and emotional impact on the families who love and support them.

For Dr. Kelly Schwartz, PhD, an associate professor at the Werklund School of Education, the phrase “ultimate sacrifice” has taken on new meaning through his research, relationships, and engagements with Canadian veterans and their families. The words now serve as a powerful reminder, he says, “to consider not only the devastating physical losses we have sustained, but the daily relational and psychological losses experienced by thousands of veteran families across Canada.”

Creating spaces for the voices of families

Since 2015, Schwartz, who is also a registered psychologist, has been exploring the impact of military-to-civilian transition on CAF family members, specifically those living with veterans who are experiencing mental health problems.

“Our study focused on capturing the voices of family members as they transitioned alongside the veteran,” explains Schwartz.

The researchers received significant interest from family members of veterans in every province across Canada. “Our focus was to hear directly from the family members — parents, adult children, siblings, grandparents — about this transition,” says Schwartz, “and because the veteran was experiencing moderate to severe mental health problems, family members were eager to ‘tell their story’ as they navigated the transition with the veteran.”

The challenges of military-to-civilian transition

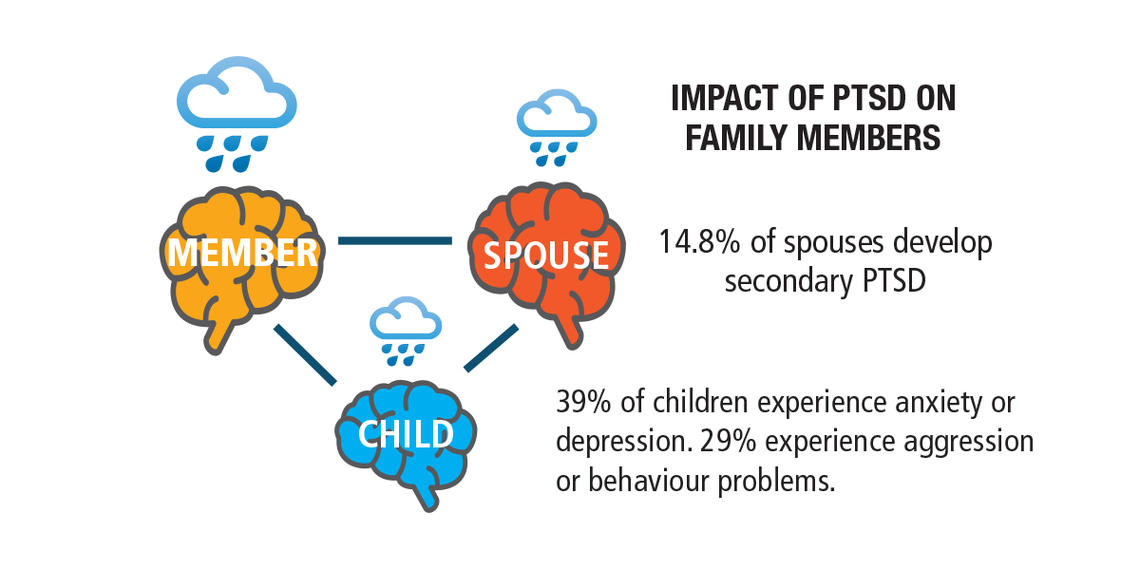

In a report produced last spring for Veterans Affairs Canada, Schwartz and other researchers found impacts on families of veterans with mental health problems that included emotional stress, relationship tensions, and financial stress as the result of changes in employment. The team learned that spouses double as caregivers to the veteran, daily buffering the veteran’s internal and external stresses, and often experienced burnout and other health conditions, as a result. Some spouses experienced a loss of identity and suffered from both social and geographic isolation. Children, too, were impacted, with research finding they experienced emotional and behavioural problems.

Schwartz sees much room for further work in this field — one issue are the younger families in need of support. With veterans leaving the military at much earlier ages, Schwartz points to the young families who will have to adjust to and cope with the significant changes brought on by having a parent with a significant mental health problem, like PTSD, depression/anxiety, or substance addiction.

“We are treating veterans in their 20s and 30s with severe physical, social, and emotional injuries,” he explains, “and knowing the long-term impact of this on families — particularly children — is still very much ‘under construction’.”

But the psychologist also underscores the resiliency of the children and youth in military-connected families and points to promotive factors such as schools, teachers, identity, spirituality, friendships, and other adult relationships, like coaches and mentors, that can help support youth.

“These factors not only protect them from harm and risk, but also develop abilities and attitudes that spur thriving outcomes like leadership, tolerance, civic engagement, and good physical and mental health,” Schwartz says, emphasizing the hope he has for the future of military families. “We certainly do need to provide care and support for those who are in distress, but we also need to study and apply early interventions that prevent and promote health development.”

Family supports and reason for hope

While these families continue to find assistance through informal channels, such as family and friends, formal supports are also accessed through Veterans Affairs Canada and other military related organizations. Family members reported positive outcomes as a result of participating in programs and/or receiving services. However, for some, access was affected by social and geographic isolation, lack of high-quality information available about interventions and supports, administrative delays, system navigation issues, and eligibility requirements.

Participants suggested that future programming offer more holistic interventions and supports that focus on the psychological, relational, and material needs during the veteran’s transition. They specifically recommended family-centered practice that would enhance the accessibility and relevance of the interventions being offered.

Schwartz says this is essential. “The seriousness and intensity of family impacts uncovered through this study strongly suggests that a proactive approach to service delivery is warranted, balancing the fragmented programs and policies currently in place to support veterans’ families.”

Overall, Schwartz is hopeful that veterans with mental health problems and their families are drawing the increased attention of researchers such as the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research. The institute has grown to 42 member universities since 2010, including the University of Calgary. The institute continues to provide support for a multitude of studies, along with a significant push for research with military-connected families, thanks to funding provided by new organizations like True Patriot Love and Wounded Warriors.

“It is an entirely different landscape for research now than it was even 10 years ago,” Schwartz adds.

In the last three to four years, Schwartz says there has been a significant change in the supports and services provided to families. With increasing access to these, researchers believe it’s important to ensure interventions are evidence-based, with data proving they are a positive and effective support for families.

As a researcher and psychologist, Schwartz has found their willingness to share experiences of living with a loved one impacted by war particularly humbling. “To hear the raw emotion of family members who are sharing both their desperation and their hope was absolutely sobering and heartening at the same time,” Schwartz says, referring to the personal impact the research has had on him. “Their stories challenged my understanding of how the human spirit is capable of withstanding incredible negative forces. The respect I have for these families, particularly the spouses couldn’t be higher.” negative forces. The respect I have for these families, particularly the spouses couldn’t be higher.”

Children in families with a member in the military may be at greater risk of mental health disorders

Research shows that families of veterans with mental health problems can be significantly impacted