Oct. 19, 2018

Diagnosing Maud

One day in the late ‘90s, Dr. Dianne Mosher, MD, walked past a bookshop in Nova Scotia when a certain book cover caught her eye. It was the front cover of The Illuminated Life of Maud Lewis by Lance Woolaver.

Mosher, a Calgary rheumatologist and member of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health at the Cumming School of Medicine, was struck by the figure on the cover. It featured a photo of a diminutive woman with a small chin, hunched shoulders and deformed hands.

“I had heard of Maud Lewis, but didn’t know much about her,” says Mosher, recalling the discovery years later. “I looked at the photograph and said to myself, ‘Oh! Maud Lewis had severe juvenile arthritis.’”

Little did Mosher know this was the first time anyone had diagnosed the famous Canadian artist with the disease — more than 25 years after her death.

A Canadian Icon

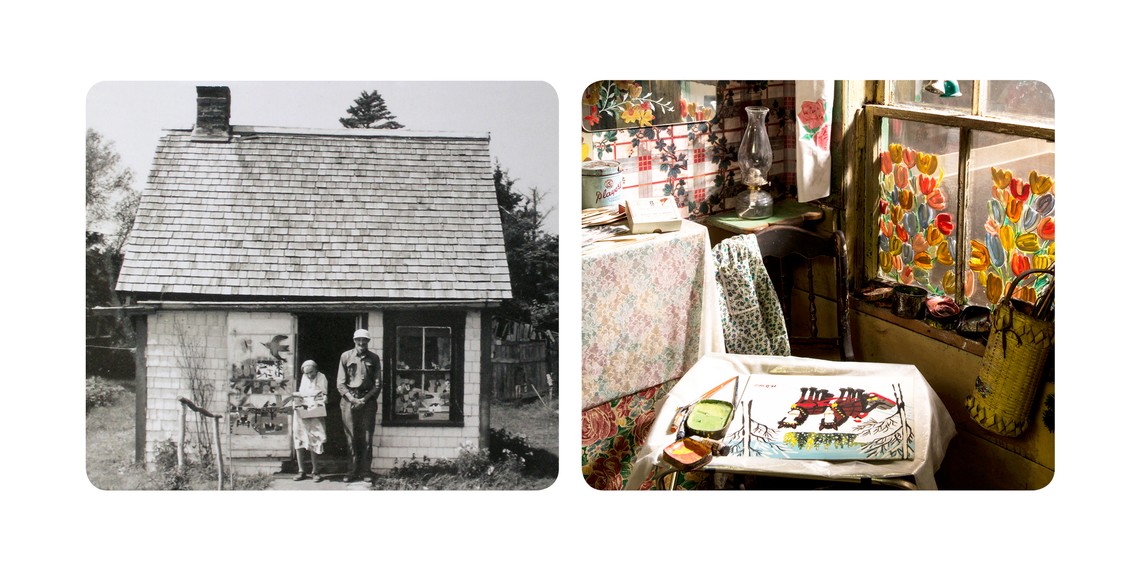

Born in 1903, Maud Lewis grew up in rural Nova Scotia. She and her husband spent much of their lives together in a 150-square-foot house with no running water or electricity. To brighten the small space, Lewis painted flowers, outdoor scenes and animals on the walls and cabinets of their house, until almost every surface was covered with bright images. She sold small paintings by the roadside to make some extra money.

According to several biographers, it was thought Lewis suffered from either multiple birth defects or polio with some biographers even describing her as deformed. Her shoulders sloped unnaturally, one leg was longer than the other, her hands were misshapen and she had chin and spinal deformities.

Woolaver’s book recounts how Lewis missed school many times and children made fun of her flat chin.

She was socially isolated and suffered a great deal of pain.

Despite living with debilitating pain, limited mobility, impoverished conditions and social isolation, Lewis went on to become one of Canada’s most beloved artists. Today, her whimsical, brightly coloured paintings that often include flowers or animals and outdoor scenes fetch tens of thousands of dollars at auction, and she serves as an inspiration for countless artists.

The diagnosis

Inspecting the photos in Woolaver’s book more closely, Mosher became certain Lewis did not suffer from polio or birth defects, but from juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Her curiosity piqued, she contacted Woolaver to share her suspicions and he kindly shared all his photos of Lewis.

“If you examine pictures of her as a child, you will note that her chin is small,” says Mosher. “Also, her neck is bent sideways, and she had flexion contractures (permanent bends) in her right elbow and right knee. These deformities are caused by abnormal growth from her JIA and deformities from her disease.”

Mosher later presented her hypothesis at a pediatric rheumatology meeting in Toronto, where there was agreement with her diagnosis. She has since presented her findings at medical conferences and meetings across Canada, even giving presentations at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

If Maud were alive today

Today, juvenile idiopathic arthritis affects one in 100 Canadian children.

Although there are still gaps in diagnosing the disease correctly, there have been many new and promising developments in the diagnosis, treatment and management of JIA.

If Lewis as a child was seen by a family physician today, her disease would be more likely recognized. She would be swiftly referred to a pediatric rheumatologist and started on one of the many therapies that effectively control the disease.

“If she were diagnosed as a child now, all of her deformities would likely have been prevented. Her chin and jaw would have been more developed, she would be taller, and her social interactions would have been far better,” says Mosher. “Maud Lewis was not my patient. In fact, she never even saw a rheumatologist. Her story is a portrait of a hero while also illustrating the natural progression of inflammatory arthritis without treatment.”